Christopher J. Phillips is a historian of science at Carnegie Mellon University. His research is on the history of statistics and mathematics, particularly the claimed benefits of introducing mathematical tools and models into new fields. He is the author of "Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know about Baseball" and "The New Math: A Political History," and his work has been featured in the New York Times, Time.com, New England Journal of Medicine, Science, and Nature. He received his Ph.D. in History of Science from Harvard University.

Terence Moore (@TMooreSports) is a national sports columnist and commentator who is a regular television contributor to CNN, ESPN "Outside the Lines and MSNBC. He also is a columnist for SportsonEarth.com, MLB.com and CNN.com. In addition, he does television work for the NFL Network, and he appears every Sunday night on a locally top-rated show in Atlanta.

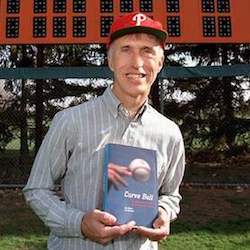

Jim Albert, co-author of Curveball: Baseball, Statistics and the Role of Chance in the Game , editor of the Journal of Quantitative Analysis and Sports , and professor of statistics at Bowling Green State University will join the Stats and Stories regulars to discuss why statistics and baseball have been linked for decades and how this connection has strengthened with the growing presence of sabermetrics in player and team management.

Episode Description

Welcome to Stats+Stories today we are trying something a bit different, with Major League Baseball’s opening day just hours away from the release of this episode we thought we would go back into the vault and throw some old school Stats+Stories baseball episodes at you. The first of which is as far back as you can go into the Stats+Stories archive, our first episode with former host Bob Long former panelist Richard Campbell, and guest Jim Albert with, “Baseball and Statistics”

The second episode features Terence Moore. Moore, who has worked at Atlanta Journal Constitution, CNN, ESPN and other notable outlets had a lot to say about “Reporting On Sports In The Digital Era” .

Last but certainly not least, we have a much more modern episode of the show which ironically happens to be about the oldest “Numbers Behind America’s Pastime”. Christopher Phillips joined us in episode 177 to discuss the entirety of baseball history from the first big league reporter from the early 1900s to the moneyball craze over a century later.

+Full Transcript

Bob Long: If you've ever listened to major league baseball, you probably know play-by-play announcers love to just pepper you with lots of statistics. It used to be you'd only hear about things like batting averages, homers, pitcher's earned run averages, but today the stats have become much more sophisticated, like how often does the batter get a hit when the bases are loaded? I'm Bob Long, welcome to Stats and Stories; it's a program where we discuss the statistics behind the stories, and the stories behind the statistics. Our focus this time is on America's favorite pastime, baseball. But before we talk to our special guest for today, we wanted to find out about baseball stats more, and how they've changed so dramatically in recent years. So reporter JM Rieger gives us a few examples.

JM Rieger: In baseball, traditional statistical measures of a player's ability have always been the norm, but Miami University Statistics Professor Doug Noe says statistical models have changed not only how fans watch the game, but also how teams manage it.

Doug Noe: The role of statistics started off as being a very, very descriptive role, and over time it's gotten to be a more, much, much more analytical type of role that helps people not only to tell what happened, but also to make decisions about what they should do.

JM Rieger: VORPs, WHIPs, and WARs have replaced traditional measures in America's pastime. Not actual war, but wins above replacement, which shows how many wins a player gives a team compared to another player. WAR took center stage in the American League MVP race last year. Detroit Tigers third baseman, Miguel Cabrera, captured the Triple Crown for the first time since 1967, and although Cabrera ultimately won the MVP as well, Los Angeles center fielder and Rookie of the Year, Mike Trout, almost stole the show, holding the advantage in one distinct area, WAR. Noe says the 2012 MVP race speaks to a larger trend in baseball.

Doug Noe: Different looks at what you decide to value then kind of get you into the argument of who is more deserving player for Most Valuable Player. Before some of the more interesting analytical work came along in the last few decades, I think that it would have been a near unanimous decision that Miguel Cabrera, the Triple Crown winner, would be the Most Valuable Player.

JM Rieger: However, had Trout won, it would not have been the first time a Triple Crown winner did take home MVP, as Hall of Famers Lou Gehrig and Ted Williams failed to do so. Miami sports information director, Jim Stephan, says statistics are just one part of the picture.

Jim Stephan: A player still has to make plays. If you are 0 for 10 against left-handed hitting, you know, if you go up and get a hit, then it's all out the window, now you're 1 for 11 and who cares, you just got a hit. So you still have to perform; the stats are an indicator of how you have performed, but it's an indicator.

JM Rieger: And if 2012 is any indication, fans will likely not reach a consensus on how to judge a player's value any time soon.

Bob Long: Our thanks to JM Rieger for a, kind of a thought provoking piece to get us started here today. Joining us for Stats and Stories are regular panelists for our show, Miami University Statistics Department Chair John Bailer and Journalism Director Richard Campbell, and our special guest today is Jim Albert. He co-authored a book called Curveball, which really delves into the stats of baseball. He's also a statistics professor at Bowling Green State University. You know Jim, I grew up in the '50s with a mother who loved baseball, this was back in the day when the Cleveland Indians were a good team, but I learned from her all about batting averages, home runs, and I think back then we had the discussions of whether a guy like Ted Williams should be the MVP, as well as winning the Triple Crown, but today it just seems like there's so many more stats out there that are used. Am I correct about that? It just seems like it's changed dramatically.

Jim Albert: Well I think now there's a lot more different ways of measuring people's contributions, especially in defense and pitching. I think we understand a lot more about that than we used to. And to me, it just adds to our enjoyment of the game; we understand these players better.

Bob Long: It seems to me that there are some fans that just love all kinds of stats, so adding a new level doesn't really bother them. I suppose there are other people though that never get into the stats at all.

Jim Albert: That's true, I think especially when you go to a game and look at a scoreboard now, when someone comes to bat: they give you stats. You want to get an understanding about how good the player is, and I think adding these additional measures gives you a better understanding of what they're contributing to the team.

John Bailer: One of the things that I've seen is that baseball seems to be much richer in terms of the statistical information that's part of it. As well as all the work in baseball that you've done, as editor of the Journal of Quantitative Analysis and Sports, you probably see lots of other applications, but I was curious if you could comment a little bit on why baseball has been so rich in this tradition of use of statistics and summary of performance, and other sports seemed to have somewhat lagged behind.

Jim Albert: Well, I think when the game started, this is back in the 19th century, I think they wanted to make it more credible and by collecting statistics from day one, they started to collect things like runs, and that was collected; batting average is a very old measure. And also, I think baseball has a very nice, discrete structure, so it lends itself well to statistics because you've got a basic confrontation between a batter and a pitcher. A basic result, you have three outs in an inning; you have nine innings. Other sports, like basketball or soccer, are much more continuous in time, so they're much harder to quantify.

Bob Long: That's kind of one of the things I was wondering about too, because it seems to me in baseball there's just more, as you mentioned, that individual, man-on-man, kind of confrontation, where there's so much more team elements to other sports, not that there aren't in baseball, but there seem to be more of that in baseball.

Jim Albert: Yeah, like in basketball, for example, a shot is scored, but of course maybe the person made the shot because of a good pass. Well in baseball, when a person hits a home run, well clearly that contribution was made by the hitter; it wasn't a teammate, so it's a different kind of thing.

John Bailer: Have you seen, over time, an evolution of some of the defensive and pitching summaries, more so? Because early on, it seems the history has been with the offensive summaries, that they were very rich and pretty minimal, maybe errors on defense or runs allowed for a pitcher.

Jim Albert: Yeah. I think, for example, fielding percentage has been the classic measure of a fielding performance, and that basically says of all the balls you played, what proportion did you make successfully? And of course, it ignores all the balls that you didn't play, all the balls that went beyond your range. So actually people understand that fielding is a lot more about range than actually catching a ball or making a play that is hit to you, so now we're actually able to measure where fielders move. We can actually quantify the movement and we have a much better understanding about range.

Bob Long: That was one thing I know if you went back and looked and had a third baseman who had five errors in a season and said, "Wow, he was a great third baseman," but if there were a lot of balls that he didn't get to, he wasn't such a good third baseman after all.

Jim Albert: Yeah. You can imagine if you had a third baseman that just stands still and doesn't move, well he'll do great at balls that are hit to him, but not be very useful to the team.

Bob Long: You're listening to our program, called Stats and Stories; our discussion today focusing on baseball and the importance of statistics. Our regular panelists are Miami University Statistics Department Chair John Bailer, Journalism Director Richard Campbell, and again our special guest Jim Albert, who co-authored a book called Curveball and he's also a statistics professor at Bowling Green State University. Well, you know, we thought it would be fun to go out and we sent our Stats and Stories reporter Colleen Rasa out to talk to people, many of whom really didn't know a whole lot about baseball; maybe they watch or listen to it a little, but they're not die-hard type fans. We wanted to just know what they knew about stats and their relevance to the game of baseball.

Woman on the street #1: To keep up with the players and track the teams, I guess.

Man on the street #1: Batting average. There you go, batting average.

Woman on the street #2: I only know one thing, and that's RBI, so I guess all of the rest of it is confusing.

Man on the street #2: RBIs, uhh, it's basically when someone's on base and another batter hits that baseball and the other person scores; it's considered an RBI for the person that hit the ball, even if they got out.

Woman on the street #3: What is an ERA even? Who knows?

Man on the street #3: I think it's just a good way to track how the players are doing on an individual basis.

Woman on the street #4: When you bunt the ball, it's not really a stat, but when you bunt the ball sometimes it can count, and sometimes it doesn't, and it's confusing to me.

Man on the street #4: ERA: Errors per game, for a pitcher. Depending on how many errors, how many hits they get on the field, if someone gets on base, it's an error.

Woman on the street #5: I don't know. I don't know any of the stats; I'm a hockey fan and I watch hockey.

Man on the street #5: They do a lot of new stats these days, with like the submetrics, that I don't really get into or pay attention to.

Woman on the street #6: I know what like .500 is, like if they bat .500 it just means that they strike out as much as they get a hit.

Bob Long: Well there's a few things that are just slightly off base. Gosh, a stats guy like John Bailer, that's got to drive you nuts, "submetrics." I think they meant sabermetrics.

John Bailer: Yeah, yeah. Close, but no cigar. And I guess it's appropriate that the show has somebody starting in an off-base position here. So Jim, could you talk a little bit about the sabermetrics? Where did that come from? And what exactly does the "saber" mean in this context?

Jim Albert: Well, there is a group of people in the 1970s that were especially passionate about baseball, and passionate about the history of baseball, and so they started an organization called SABR, the Society of American Baseball Research. So about that same time, Bill James was talking about quantitative analysis so it seemed natural to use the phrase "sabermetrics" to correspond to the quantitative analysis of baseball.

Bob Long: I'm just kind of curious, when did you get started? When did you get interested in all of this?

Jim Albert: Well when I was growing up, I loved baseball; I was a baseball fan and I liked math and I liked to play probability games in my basement. I played games like All-Star Baseball and Strat-O-Matic and would play a whole season and keep stats. It was fun, I really enjoyed learning about the players and knowing about their statistics.

John Bailer: Yeah, it's neat to see. Is there something equivalent to sabermetrics in other sports? I don't know of anything that has that kind of "metrics" before it in other sports.

Jim Albert: Well, I think what's happening in other sports is they're basically following the lead in baseball. For example, situational stats, which are very popular in baseball, now we're talking about situational stats in football and basketball. So it's more than how you do; it's how you do in special situations.

John Bailer: So can you give an example of situational statistics and summaries that you might see in a different sport?

Jim Albert: For example, there's this home versus away affect; how you perform at home games versus away. Generally, the home team is more likely to win and the advantage of the home team depends on the sport. In baseball, it's relatively small; in basketball, it's larger. We talk about how people perform in the clutch. You know, when it's an important situation in the game, how do you do? And people like to think that people have what is called "clutch ability," the ability to do a special performance when it's an important situation. Reggie Jackson, he's called Mr. October because he performed well in October. Dave Winfield was called Mr. May because he didn't do as well during the World Series. So to me, I don't believe in "clutch ability," I believe in "clutch performance," but I think people like to talk about that because that indicates something about the value of the player.

Bob Long: Richard Campbell?

Richard Campbell: Jim, how much does this rise in keeping track of numbers and statistics on players, how much is it affecting the old coaches and managers that used to make decisions just based on their gut and go with their heart? And do we actually have statistics on how often they're wrong, and how often they're right in making those kinds of decisions?

Jim Albert: I'm sure they do, and what's interesting about baseball is that some teams have really embraced the sabermetrics movement, and I think it may be that some teams do use quantitative analysis when to decisions about managing, and other teams probably don't. They might use metrics more for scouting players, especially when they draft players, but I think a lot of the managing going on in baseball is the same as it was thirty years ago.

John Bailer: As a follow-up to the use of some of these statistics and summaries, there's been controversies associated with things like steroid use and abuse by some of the players. Can you talk about how some of these summaries have been used to perhaps support or identify something in a performance that you wouldn't expect?

Jim Albert: Well if you look at Barry Bonds, and look at his performance through his career, it is very interesting because he hit his peak and then started to die down and all of the sudden, his performance enhanced dramatically close to forty years old. I'm not saying it was steroids, but there was something that caused that change, and you can see the effect statistically.

Richard Campbell: As the story guy here, the guy from the humanities who also is a big baseball fan, I argue when I talk about narrative that people are drawn to sports because they are organized like stories, they have a beginning, middle, and end; they having rising and falling action; they have good guys and bad guys; and most of all, conflict and dramatic tension. So my question here is where does stats fit into this picture? How do they enhance the sort of narrative of the game? Because we just heard from all these students, and the general public, who appreciate baseball at a level that is sort of not statistical, and I'm also fascinated, as a humanities guy who is an English major, I kept track; I love the numbers; I love reading statistics. There's certainly something that enhanced the game for me, following numbers in sports.

Jim Albert: I think a box score of a baseball game is the story of the game. I also think that some stories are defined by statistics. For example, you think of DiMaggio, and you've got to think about the 56 game hitting streak; that was his story. Think of Cal Ripken and his however many consecutive games he played. You think of Ted Williams hitting .406. That's a great story: last day of the season and the manager was suggesting he be benched because he might fall below .400 and Ted Williams said no. He played a double-header and actually raised his batting average on the last day; those are great stories.

Richard Campbell: The box score story is interesting. I remember; I still have them. In 1975, I clipped every box from the Cincinnati Reds year because I thought, "This is a good team and they're gonna go." And I saved every one, and I still have them. And it does, you can look at them in order and read them and have a pretty good sense of what the story was.

Jim Albert: If you go to baseballreference.com, which is a wonderful website for baseball stats, you literally can revisit all these legendary box scores.

Bob Long: I think that's kind of interesting, though, because I remember reading a book that Sparky Anderson wrote after the Tigers went to the World Series, when he had switched from the Reds to the Tigers. But it seems to me that he had a lot of box scores in there, but it seems to me that true baseball fans really fall in love with that element of the game.

Jim Albert: Yeah. I remember, I grew up and I remember so well Jim Bunning. I was a Phillies fan and Jim Bunning pitched a perfect game on Father's Day, and I still remember that box score. I remember where I was when I watched the game on TV, but I think it's a beautiful box score because you see all those zeros. Bunning faced 27 hitters. It was perfect.

Bob Long: You don't find a box score that looks like that too often.

John Bailer: So which of these records do you find as kind of the most dramatic story? And sort of related to that, which do you think is going to be the hardest to break?

Jim Albert: I think the 56 game hitting streak is probably one of the hardest ones to break. I think nowadays it's difficult to even have the opportunity to hit during a game, so now I think there would be a lot of pressure. I think once a player gets into a streak, there's a lot of discussion about it and there's a lot of pressure to continue hitting. That's a remarkable record.

Bob Long: We'll take a quick break, but you're listening to Stats and Stories, and of course we are focusing, for this week's show, on the role of statistics in baseball. I'm Bob Long; our regular panelists that you've been hearing, Miami University Journalism Director Richard Campbell, Statistics Department Chair John Bailer, and our special guest today, Bowling Green State statistics professor Jim Albert, who is also co-author of the book Curveball, which again delves into the use of stats in baseball. Again, our own Colleen Rasa went out and was curious if fans really understand what the baseball statistics are being used for today.

Man on the street #6: It's money based, too. Whichever team has better players and better stats, they're going to make more money and have more for their program.

Man on the street #7: They're used to record pitching, fielding, batting, percentages of games that are played, percentages of people that show up that don't want to pay $400 for a seat.

Woman on the street #7: They are used to follow which player is doing the best, or which team is doing the best, the way I see it.

Man on the street #8: Typically, whoever has the better stats will bring the team along to the World Series.

Man on the street #9: It tells you who the key players are on the lineup; who's going to be first, who's going to be second, who's going to be third. It gets you an idea of how the team's going to do through the year.

Woman on the street #8: Um no, because I'm a baseball fan in the fact that I like to go to the Reds games, we sit in the five dollars, bleachers, we drink beer, and so if they get a hit, it's fun, but if they don't, we boo and hiss. Stats make no sense to me.

Bob Long: I can't watch a baseball game like that. That's just not part of my DNA. But I do think it raising an interesting issue, because we kind of heard the word "money" mentioned in there, and I think that's another thing that dramatically changed what's going on because, I, as a fan, may use baseball stats to look at one thing, but managers and owners look at it in a much different way. And of course, agents of players also use it much differently today.

Jim Albert: Yeah, I think what's happening now in baseball is that players are moving a lot more between teams because it's all about contracts. I follow the Phillies, and everybody is talking about Chase Utley because his contract is up at the end of the year, so people are wondering if he will be worth resigning after the season. And unfortunately, that's a big part of it, and great players will move. Albert Pujols; hard that he would leave the Cardinals after so many years, and it all came down to money.

John Bailer: Do the players start to use some of these new statistics to argue for value? I mean it seems like there's sort of two levels to this: one is the teams that are deciding who to try to acquire, but also, are the players able to leverage their performance on some of these metrics?

Jim Albert: I'm sure they are very aware of these performances, and they use it as leverage for the contract. It's an important part of their game now.

Bob Long: Richard?

Richard Campbell: In your book Curveball, you make a distinction between sports statisticians and professional statisticians, which is kind of interesting. Could you talk about that a little bit?

Jim Albert: Well, I think there's a confusion about the word statistics, because we think of the people who are just tabulating the data, and they're called statisticians. But to me, a statistician is somebody who actually interprets the data and tries to draw conclusions, or uses for prediction, that's more what we're talking about. There will always be that confusion because we use the word in two ways.

Richard Campbell: You talk about the professional statisticians, like you and John, use models as a distinction between information. Give us an example of that. You talked about one example, which is the old games some of us used to play.

Jim Albert: Well for example, baseball competition, I mean, basically teams have different abilities, but the point is they play each other, and there's a role of chance involved in who actually wins the game. So you can use a model to describe the role of chance. You can actually quantify how much, you can actually quantify "what's the probability that the best team, the team with the most talent, wins the World Series?" And that's done by using a statistical model.

John Bailer: One feature that I thought was interesting in the comments was the idea that the team with the best stats will win. Do you have classic examples of some of the traditional statistics where a team that looked really great on some of the traditional summaries just didn't perform well, but the new metrics might highlight that and explain it?

Jim Albert: Well for example, batting average is not really a good measure because it ignores things like getting on base with a walk, and really the key issue, there's two issues: one is that you want to get on base, and on base percentage measures that, and you also want to advance runners that are already on base, and like a slugging percentage measures that. So unless you talk about both of those things, you really are missing out on what's important in baseball scoring.

Bob Long: I'm kind of curious, though, there are some stats that I wonder how valuable are they. You'll hear a play-by-play announcer, for example, say "Well, so and so only bats .125 when the bases are loaded," like they are at that particular moment. Does that really mean as much, because maybe that guy, if he's batting .125, had only been to the plate eight times with the bases loaded, which doesn't seem like much of a measurement that you can use.

Jim Albert: What they never tell you is the sample size. And sometimes, the sample size is so small, so really, with small samples, you get a lot of variability. This also happens with pitcher-batter match ups. Sometimes you'll have a certain batter who does really well against a certain pitcher, but that's over many years, so really it's not a very meaningful statistic, but unfortunately, managers often make decisions based on that kind of data.

Richard Campbell: My job running the journalism program here is to help our students think about incorporating numbers and data into stories and how do you tell stories that use numbers and data? In general, how well do you think sports reporters do using stats and numbers, and what do you think they do well, and what aren't they doing so well?

Jim Albert: Well, I think it's harder for them to use more modern statistics, because they're not really able to understand what they mean. For example, if I tell you that an OPS value was 1.200, you probably wouldn't understand that, but a batting average above .400, there's certain statistics in baseball that have a very strong understanding. A .400 batter is a great hitter, winning 300 games in a career is a great accomplishment, 20 wins in a season for a pitcher is considered good. So I think these always will be easy to talk about because everyone understands them.

Bob Long: I know one that I've got to throw in today, and I was just reading up on this today. George Brett, who was one of the last guys to come close to hitting .400, I think he finished around .390, but at one point he wasn't doing too well and his teammates were making fun of him that he was approaching the Mendoza line, referring to Mario Mendoza, a short-stop who was a light hitter who kind of lowered the benchmark. He couldn't even hit .200, and the .200 level has kind of become a benchmark. How much does that happen that you see certain things that really aren't necessarily statistically backed all of the sudden become a very popular thing in the media that everybody refers to like that?

Jim Albert: For example, currently, we think that 100 pitches in a game for a pitcher is one of those things that you don't want to break. Once a pitcher throws 100 pitches, he's out, and I really think that in five years, we're going to change that; it won't be 100 pitches anymore. I think we're still learning about pitcher fatigue, and we're so worried about injuries. But I don't really think that there's any evidence to say that 100 is the right number, but once those numbers are used, they become the number that everyone thinks to use.

John Bailer: Do you think some of these new metrics that are coming about are starting, we've talked about them influencing player selection and team management, we talked a little bit about them modifying what's happening during the management of the game, game management, not just team management, where do you see the greatest opportunity for increasing the impact of these ideas in the game?

Jim Albert: Well, I think, for example, on the decisions like on how to advance runners, advancing to second base, those kind of things, I think people have to use stats to understand the value of those things. I think running in baseball is not as well understood as we'd like to think. But nowadays, there are ways of measuring the contribution of running. So it's going to be a while before those things are accepted. We still focus on things like batting; that's easier to measure.

Bob Long: Are there other areas that you think eventually, you mentioned the running aspect, other things where you think we're going to see more of that in the future in baseball? Because it seems like a lot of people think that we're saturated out right now, but do you see other things that are on the horizon?

Jim Albert: Well currently, every single pitch that's thrown in baseball is photographed, so we have measurements on the trajectory, the movement of pitches, the type of pitches. Everyone is talking now about how Roy Halladay's pitch speed. That's been important. I think what's going to happen now is we're also starting to measure things like fielder location, locations of hits, we can actually quantify, we can talk and say this person hit so many line drives. So we're starting to learn even more about baseball.

John Bailer: Question, what sport do you think is going to be the next one that's going to be majorly impacted by the analytics of sports?

Jim Albert: Well, I think that the sport in the world that's the most popular is soccer, and I think that's the area that I think people are trying more and more to use baseball types of measures, but it's much harder to quantify. I think the fact that they're measuring the spatial locations of players is going to be a positive thing and eventually will get better measures.

Bob Long: Jim Albert, thanks so much for sharing your insights on baseball with us on this edition of Stats and Stories. We'd like to invite you to check out our website. It's statsandstories.net, and be sure to listen to future editions of Stats and Stories, where we'll discuss the statistics behind the stories, and the stories behind the statistics.

Bob Long: Baseball fans used to sit by the radio listening to their favorite major league team, then along came television to bring us the visual image. But today we have digital technology that brings us so many rapid changes it sometimes makes your head swim. You can see any game you want now streaming live on the internet and "wa-lah", even on your phone app. The digital world also has brought us a raft of new statistics to help us analyze our favorite players and our favorite sports. I'm Bob Long, we want to welcome you to Stats and Stories it's a program where we look at the statistics behind the stories and the stories behind the statistics, and our topic today is how the digital technology has complicated the life of sports journalists. Before we talk to our special guest, Stats and Stories reporter Max McAuley talked to a couple of sports journalists about how they've been impacted by digital reporting and sports analytics.

Max McAuley: Modern athletes are jumping higher, running faster and playing better than ever. Year after year athletes break seemingly impossible records and compete at higher levels, to keep up journalists and statisticians are changing their games as well. Modern sports reporters are adapting to master the immediacy of new online digital media, and statisticians are measuring and analyzing more complex metrics to try to figure out what makes today's athletes so great. Chris Rose is a sportscaster for the MLB and NFL networks. He can attest to many of the ways that digital media has recently changed the face of sports journalism.

Chris Rose: Five years ago people who covered the beat, they didn't have to worry about Twitter because, you know what, the next day in the paper, people would read it then. But now people have a need to know the information right now.

McAuley: Rose uses digital media to keep his shows as up to date as possible.

Rose: I'm getting ready for my baseball show today, what I do is check Twitter, because all the beat writers have already talked to the manger, they've made a run through the clubhouse, so anything interesting is there in 140 characters for me to absorb and boom, it's at my fingertips, and it's a tremendous resource for me, and we find good stories for our show that way.

McAuley: Alex Butler is a contract writer for The Miami Herald in Florida. Like many other newspapers The Herald has had to expand to virtual outlets as well.

Alex Butler: There is a lot of focus now on the digital side of it, with the online media, I've come to really appreciate that where I get to incorporate my Twitter account a lot, and talk about the athletes and tag the athletes engage the fan-bases and communities.

McAuley: Butler points out those online technologies have created two-way information channels between media outlets and their audiences.

Butler: We use different websites that use algorithms to see how many people are viewing our articles and how they're interacting with the article specifically, what they're clicking on within the article, how much time they're spending on the article, it's much more interactive now and there's a lot more things to think about than just subject matter, it's how you actually write about the subject matter.

McAuley: One problem Butler has with the digital age is when the public sides with the memes over the media.

Butler: I see people blame the media for everything and I get kind of frustrated with things like that when people are starting to believe pictures with text over them over quality journalism because they think the media's pure evil.

McAuley: Chris Rose has worries about digital media as well. He says the focus on immediacy has shifted both readers and writers away from focusing on factuality.

Rose: When you have social media, people are going to read things the way they want to. The danger of it is, not everything gets checked the way it should.

McAuley: Rose also says he likes the argument arising from the new emphasis on deeper statistics.

Rose: Well we really live in an analytical world now; it's just a part of how we evolve, and I think it's been a fascinating discussion, you know, there's just more information for people and I'm a big fan of that.

McAuley: Alex Butler agrees, he says statistics have the ability to see things that our eyes might miss.

Butler: I'm kind of a statistics guy; I think it's interesting to tell a different story than the obvious one.

McAuley: Butler says it's still important for media outlets to tailor their content to their audience.

Butler: Different newspapers, I think, have different goals, when that's concerned. Like a small area like Dayton, people there might care less about every statistic in the game and more about a particular player that they find fascinating.

McAuley: Chris Rose says most sports organizations are still trying to figure out how to best to apply these new measures.

Rose: The argument is how do you build a team, and how much do you put on metrics.

McAuley: The world is starting to realize that there's a lot more to sports than just scoring points, and Rose says some teams are willing to pay millions for it.

Rose: Jason Heyward, who has been in one All-Star Game, who hasn't hit more than I think sixteen homers in a year, who hasn't driven in, I think, more than like seventy-five runs got almost two hundred million dollars. Well, he's a twenty-six year old outfielder, the best defensive outfielder, according to the metrics, who runs the bases very well, according to the metrics. So, how much do you put into valuing that, as opposed to what your eyes just tell you on a baseball diamond, or what a guy brings into a clubhouse. Heart, the ability to bring guys together, all that has a dollar value, we just don't know what it is.

McAuley: For Stats and Stories this is Max McAuley.

Long: Thanks Max and joining me now on Stats and Stories are our regular panelists, Miami University's Media, Journalism and Film Chair Richard Campbell and our Statistics Department Chair, John Bailer. And our special guest today is National Sports columnist and commentator, Terence Moore, he's a regular contributor to ESPN's Outside the Lines CNN, MSNBC, and the NFL network, he also writes for earth.com, mlb.com, and in his spare time he also teaches a journalism course, here at Miami University, his alma mater. Terence, welcome to the show.

Terence Moore: Thank you.

Long: I want to go back in time, because you know when I'm older, you know, older folks, we always go back in time and look at the way used to be, but you know, you spent what, about 25 years at the Atlanta Journal Constitution and back in the old days, hey if you were a sports writer, you were a sports writer and you wrote your article or column and that was it, today there are so many other things that you have to think about.

Moore: Yeah, there really are. It was mentioned earlier about Twitter, for instance, any kind of social media outlet, you've got to be very good at shooting video. It's more than just the writing aspect of it that you've got to be involved in. And that's why, if you look at it… when I first came out of Miami back in May of 1978, you basically had sports writers, the average age was deceased. Now the average age of a sports writer is like right out of the baby crib, because you got to be able to do all these things, you go to be able to keep up with modern technology, and it's a whole different world.

Long: Sadly, I know so many journalists that I knew, that have left the business because they just got frustrated with things that they felt detracted from the quality of the work that they did, because now they got to, as you said, shoot video, do all these other things, that they didn't use to have to do.

Moore: Oh sure. You know, and the other aspect is too, is that it's different with the players. Back when I was first starting out, you could really get a chance to know players, and know coaches, but because of so many different reasons now you really don't get a chance to know the guys. And a lot of that goes back to what we were talking about with the social media. To give an example, I had a long talk to the other day with a guy named Claude Felton. Claude Felton is the Sports Information Director at University of Georgia, and Claude is the last of a dying breed of SID's, as we call them, and I've often told Claude that I want to come and take his temperature every ten minutes to make sure he can be around a little bit longer. One of the things Claude and I were talking about is that in the old days you knew who all the sports writers were; you knew what they were all about. Now you've got all these entities, all these internet sites, all these different sports outlets, you don't know whose who, and at any given time they can tweet something out there, and if you're like a Sports Information Director or a Public Relations guy in the National Football league or what have you, you don't know where it came from, whereas before you can see the writer over there from the Atlanta Journal Constitution, or the Cincinnati Enquirer and call them in say hey that's wrong could you correct this? Now you've got all these anonymous sources out there, and people… it's very difficult to track down.

Long: Richard Campbell, go to you for the next question.

Campbell: Terrence, good to have you here. With all of the transition you've made from the print world to the digital age, I know one thing that I hear you talk about is the importance of storytelling, as a way to sort of cut through, and get an audience, attract readers. What has changed for you in terms of how you think about, and figure out what the story is that you're going to tell.

Moore: Storytelling is huge, and always has been huge from a newspaper standpoint, magazine standpoint, TV standpoint. But with the society that we have today, where everything is quick and easy, the storytelling has gotten quicker and easier because of the attention span, and it's because of…and let's go back to the Twitter phase. You know, you've only got so many characters, what is it 140, 150 characters in order to write something, and that has transcended down into everything in journalism. Quick and easy. I write for…one of the entities I write for is MLB.com and I just had a discussion with one of the bosses the other day and he was telling me, that they love what I do, but can you give us more of these top 10 things, like the top 10 reasons Willie Mays was the greatest center fielder of all time, the top 15 reasons why Candlestick Park was the worst ballpark in major league baseball history, and that sort of thing. Quick and easy. Just get to the point and move on, because that's the attention span again, or lack thereof of the reader, and the listener and the viewer.

Long: John Bailer, go to you for the next question.

John Bailer: So, you're talking about the stories becoming quick and easy, but that runs completely in contrast to the amount of information that's available to tell these stories. You know, you start to see information like, all the pitch locations, the speed, the summaries of every single pitch of every single game, we're hearing about now, chips being sewn into uniforms so you have GPS locations, you have true measurements of speed, or the distance traveled during the course of play. So, that seems like a real pressure, the pressure to simplify is running counter to this pressure, of more information that might have an interesting embedded in it. So, how do you address that?

Moore: Yeah, and that's another good question there, and I'll give you a bigger picture there. One of the eternal problems, and I call it a problem, that you have in journalism, particularly sports journalism, and to get even more finite, baseball, sports has always involved a bunch of numbers, baseball in particular, but as you just pointed out, the numbers have gotten more advanced, more plentiful than ever before. So, one of the biggest problems you have in journalism, I was going to say young journalists, but it's us old timers to, is getting too much information out there, because your brain will explode. Ok? It's always that constant battle as to what can you do to get the point across, but not too much. And my philosophy is always, get that one big thing and hammer it home. For instance, you take somebody like, say Chapman, the reliever for the Reds is now with the Yankees, and you know this guy is throwing like one hundred plus miles per hour and there's all kind of other metrics and statistics you can use to describe how great he is or what he does. But you know what? What people know is that he throws really hard, and the only thing they care about is the fact that he throws over a hundred miles per hour. So you can just concentrate on that. You know, how many times does he top a hundred miles per hour? Just hammer that home and forget everything else, at least in one piece, you'll be just fine.

Long: I think that brings up an interesting point too. One of the other things I see, and we talked about this the other day in a news context, but in sports too. We've always had some really great investigative journalism that's been done, and it seems like, as we're talking about this time crunch, that's kind of gone by the wayside, which is kind of a scary thing to me as a journalist, that we don't take time to really dig deeply…you do some work for Outside the Lines, which kind of does that kind of journalism, are you kind of concerned because of that emphasis on the here and now, get it done fast and get it out there on social media or on the internet that we're missing some of that.

Moore: I want to give you a classic example because perfect timing for asking that question. I just taught a course for Professor Campbell here, earlier today. And one of the questions involved what was the thing that I was most proud for having done in my journalistic career. One of which was back in 1982 back at the San Francisco Examiner I mentioned to the sports editor the decline in numbers of African-Americans in baseball. This is 1982, this is way before this became fashionable, ok? And I had such enlightened leadership back then that the sports editor said 'why don't you take a month off, and just get into the numbers and figure out what's going on here.' Ok, and at the time-let's jump ahead, right now slightly less than 8% of major league baseball is African-American. Back in'82, when I did the research, it was slightly less than 20%. So I started getting into the numbers, I started getting reports from different scouts, and one of the scouts gave me a scouting report that had a slot for race on it, which…you shouldn't do that. The NBA didn't do it, the NFL didn't do it, the NHL didn't do it, and baseball did. And all heck broke loose when I pointed this out. And this piece won a lot of awards, national, state, and that sort of thing. But I needed that month to do the research on the numbers, to find out exactly what was happening, not only in major league baseball with various teams, and through the years. I would dare say that in 2016, that's not going to happen. Because you're not going to be given the time, they're not going to tell you, 'take a month off' I was covering the San Francisco Giants at the time, you're not going to have a beat writer take a month off to do that, and to give it the time that it's worth, outside of perhaps at Outside the Lines which is why I like for ESPN Outside the Lines.

Long: You're listening to Stats and Stories where we always talk about the statistics behind the stories and the stories behind the statistics, and our topic today is the digital technology and how it's impacting the life of sports journalists. I'm Bob Long; our regular panelists are Miami University Statistics Department Chair, John Bailer and Media Journalism and Film Chair, Richard Campbell. And our special guest, National Sports columnist and commentator, Terence Moore, he just mentioned Outside the Lines but also does a lot of work with CNN, MSNBC and the NFL network, and I'll go to Richard Campbell for our next question for Terence.

Campbell: Terence, you've made a transition from being a reporter, documenting, verifying, you know, going out and finding out what happened to more analysis, opinion writing. Talk about how documentation, verifying, and the kind of skills you had as a reporter contributes to your role today where you're doing much more analysis and opinion writing.

Moore: You know one of the things I always tell young writers, is that the reporting never stops, and that's one of my biggest pet peeves of modern journalism, is the lack of reporting, and you've got to have reporting. Back when I was a sports writer, just a regular sports writer, I was noted for being a very good reporter, having a lot of sources, and the same now as a columnist, I break a lot of stories, it has not stopped. One of the things I'm proudest of… people ask me, you know in thirty plus years in the business, nearly forty years, that's why I've got the grey hair, you can't see it over the radio but I've got a lot of grey hair… is that nearly forty years of doing this I've never had an extended problem with any player, any coach, or any front office person. They'll blow up for a little while, and that's because they know that I've researched and I have my facts correct and they can't argue with my point of view, and again that goes back to numbers a lot of times, as far as proving things to be correct, and that holds true whether you're talking about opinion writing…or at least it should hold true…whether you're talking about opinion writing or regular writing, you still have to have the reporting aspect. So, for me I believe that it's all the same thing the difference is that from a columnist standpoint you're just giving your opinion, but it's still backed up with facts.

Long: John Bailer, we'll go to you.

Bailer: So, as you look back on the sports that you've covered, I'm curious, if you'd consider, what sports do you think…other than baseball which has the longest history with the analytics part of the applications, what sports have most benefited from the additional data that have collected, and what have least benefited from the additional data that are being collected, and when you think about this, you know, think about it in light of the stories that emerged from it.

Moore: Well, you know, I think that contrary to what people think, all these sports have benefited from analytics, and I'm going to give you an example. One of the biggest things that's happening in the NBA right now, and it's a secret story, as a matter of fact I've just talked myself into a column, I'm going to write this next week, is that you've got this old-school NBA that goes the eyeball test, I think somebody mentioned that earlier on one of the tapes you had, about how a guy looks and what a guy's doing, but now you've got this new system of analytics, and this is basically, the Houston Rockets, probably are the first team that kind of really brought this to light, about how important the three point shot is for instance. And they have all but said 'we don't care about the medium range shot, no, we want three point shooters, we want either three point shooters or layups, that's it. And if you can't do those two things, we don't want you.' And this was kind of a radical aspect, as a matter of fact they started getting rid of, the Houston Rockets, their main stream type of coaches and started bringing in these number guys that can start analyzing guys in college who are able to shoot shots from a certain distance, and if they couldn't do it 'we don't care how good you are, we don't want you.' That has spread across the NBA; it's become an epidemic now, teams that were fighting that now are part of that revolution. So that's just the NBA. The National Football League certainly the numbers have always been there. You look at what goes on in the NFL scouting combines every year in February, ok, and I think one of the nicknames that they call it is the world's biggest underwear show. Where they're looking at these guys and they're testing them all kind of thing, but numbers are huge. How high can you jump, how high you can run, how…whatever it's going to be? So whatever sport you name is there, how fast can you serve in tennis? It's all a matter of how you want to use the numbers.

Campbell: Do you think we've tipped too far, I mean the old eyeball test or the kinds of qualities that a player might have that aren't necessarily measurable in those ways, are we losing sight of that, or will the pendulum swing back or do you think things have changed forever?

Moore: That's a very good question and the first part is yes. We've gone way way too far. And I'm going to give you two examples. One, "O time" I covered the Oakland Raiders, back 35 years ago, back when they were the real Oakland Raiders, I don't know who these people are now, but the real Oakland Raiders with Al Davis, some of the football fans probably have heard of Al Davis, and Al Davis was very much about the eyeball test, you know he could tell whether a guy was good or not, and those Raiders did very well. Now I'm going to give you a baseball example, there's a guy named Dusty Baker. Dusty Baker has just recently been hired by the Washington Nationals; he should have been hired by somebody a long time ago. He's been out of baseball for two years. This is a guy who was a three time National League Manager of the year and a guy who has turned teams around instantly, but he couldn't find a job for two years after he was fired by the Cincinnati Reds because, he was known as an eyeball test guy and not a numbers guy, so that was being held against him. As a matter of fact there are a lot of people who think, including Dusty Baker, that, because I know Dusty very well, that he was fired by the Reds was because the Reds didn't think he could get up to the times and become a numbers guy. Well, they fired Dusty Baker and look what they got in return, I think they probably want Dusty Baker back right now, so to answer your question, yes, we've gone too far, because we're seeing a guy like a Dusty Baker and the Dusty Bakers of the world are perfectly fine managers or other fine coaches, are being shoved out.

Long: John Bailer we'll go back to you.

Bailer: I think you're right; either extreme is probably not desirable. This is complementary information, as I look at it. There's a human element that you're gauging in some dimensions that you can't quantify, but there's complementary information, or maybe supplementary information that you can get from some of this quantification of performance. I mean now the question is, are you measuring the right things?

Moore: Yes

Bailer: I mean, so, this kind of mindless number thinking isn't going to do anything if you're not looking at something that's meaningful and relevant for performance and outcome.

Moore: Well yeah, and to piggyback on that, let's go to another sport: College Football. The most dominate team in the history of college football is present to…right now. And it really hurts me to say that because I was born and raised in South Bend Indiana, University of Notre Dame, but I have to say right now, you can make a case that University of Alabama has the most dominate college football program of all time, given that this is an era of parity have they still been able to dominate. Nick Saben being the head coach there, Nick Saben is a combination of both, as you say. He's a guy who's very much into the eyeball test but he's also into a lot of numbers. One of the things that I saw the other day is, Alabama, and I wish I could know the number off my head, has got the largest support staff of any team in college football. You know, people think in terms of a college football program or a college basketball program in terms of just coaching, there's all these other people that they're bring aboard now. Numbers people, even besides people in training staff or what have. And Nick Saben has started an arms race. I live in Atlanta Georgia right now, and one of the things… I'm always ripping the University of Georgia because they're getting all this talent, and they're getting as much talent as anyone in college football, but they have not won a National Championship since 1980, they have not won an SEC title since 2005, but they keep getting all this talent. So, they fire their previous coach Mark Richt hired a new coach now in Kirby Smart. One of the first things that Kirby Smart did was to get all these other people, numbers people and what have you. They've increased their support staff something like 75% since he's been hired in a matter of months. Guess where Kirby Smart was before he came to University of Georgia? Alabama, as defensive coordinator.

Long: You're listening to Stats and Stories and we're focusing on our, how digital technology and analytics in sports, how all of that has changed the life of sports journalists. Our special guest today is Terence Moore who's a National Sports columnist and commentator. I'm Bob Long, our regular panelists on our show are Miami University Media Journalism and Film chair Richard Campbell and Statistics Department chair John Bailer. We kind of touched on this, Terence, a little bit ago. Twitter of course, and the whole social media realm has really changed things, not always for the better. There are a lot of things that get tweeted out there that some people would love to retract but they can't. But let's talk about how the involvement of athletes in getting their message out, rather than letting people like you tell the story, how that's impacting sports journalism today as well.

Moore: Well, you know, it's killing our craft, and I'm an old timer. I believe in old time journalism, give me the old time religion, give me the old time journalism. Good reporting, good solid basics, and I hate to say it is going, going, almost gone, and Twitter is a big cause of that. One of the old time edicts of journalism is get at least two sources before you write something, that's gone. Because somebody could go out there and tweet anything, and even in mainstream journalism you're forced to follow behind that because it's out there. People don't care about you getting two sources anymore, and it's caused all kinds of problems with that. The other problem that Twitter has caused in my profession is that, it's made it very difficult now for mainstream media to break anything, because if you're an athlete and I think of Calvin Johnson, wide receiver, great wide receiver for the Detroit Lions, when he announced his retirement, or rumors thereof, Twitter. So this isn't the Detroit Free Press or the Detroit News he can just go to his Twitter thing 'I'm thinking about retiring' about whatever. So, how do you react to that? Tiger Woods ok. When Tiger Woods wants to announce anything, first of all, he announces it on his website, so he's not calling a press conference, given his life lately, I'm sure he's not going to call a press conference, but he's putting it on Twitter, he's putting it on his website, so it really has hurt us in a bad way.

Long: I was going to say it just seems to me that a lot of times that's a way to escape the scrutiny, that you pointed out would come with a press conference where I could ask you about some other stuff that you might not want to talk about, you're pretty much channeling it, here this is my announcement…

Bailer: You control the message

Long: You control the message, you don't.

Moore: Let's take it out of the sports realm; let's look at what's happening in presidential politics. Who is the number one tweeter in America now? Donald Trump. Donald Trump has figured out a way to get his message across is just to wake up in the morning…even though it's misspelled all the way through it…tweet whatever he wants to tweet, and it's out there. Whereas certainly twenty years ago, forget twenty years ago, the last presidential election cycle, you still had to go through the mainstream media. So, this has changed us forever.

Long: John Bailer, go to you.

Bailer: Ok, in your practice, how much interaction have you had with the analytics staff of different professional teams or collegiate teams? Have you ever… as part of the story as you've dug in have you ever had any interactions with these new offices.

Moore: You know that's another good question here, and to answer your question, very very little, and I want to tell you, there's two reasons for that. Number one, and by the way I mentioned the Houston Rockets, the Atlantic Hawks, have become another one of those teams, and I'm based in Atlanta, and there's a big controversy about the Atlantic Hawks about how much weight they're giving these people. But to answer your question, first of all they make it very difficult to talk to these people.

Bailer: It's proprietary development.

Moore: Yeah, they don't want you to talk to them, and they're very much, and to tell you, I know the names, and as a good of a reporter as I am and I take pride in being a good reporter, I can't tell you the faces of who these guys are for the Atlantic Hawks, I know the other guys but they're off in the distance. So that's number one, number two and sort of from a columnist standpoint, I don't know if I really want to talk to them that much, because again it gets too weighted down to try to explain that to your reader, it's just too bulky to be able to do that. I would think maybe a beat writer more so, somewhat, but even they would have a little problem just trying to get…it's too involved.

Bailer: Sure, thank you.

Long: Richard Campbell.

Campbell: Talk a little bit about…I mean part of this was discouraging right, for young reporters who want to be sports reporters, and what… they're facing a world in which stories are broken not by reporters but by the athletes themselves, so what kind of advice do you give somebody aspiring, because you are kind of an inspirational figure and a lot of people I think admire your career, and want that kind of career, so what do you tell them.

Moore: Well I've got three pieces of advice. One is drop back seven yards and punt. Number two, do something else. Seriously, seriously folks. I would say, just keep fighting the good fight. This is my constant message; I think that if you do things the right way, whatever they are, in the long run, for you, it's going to work out. Keep practicing solid journalism that's the only answer, because if you give in to this other stuff, then there's no chance. There's no chance for you, there's no chance for the profession. So, keep doing…keep going to great school's like Miami University and taking great classes that we teach here at Miami University, where you're learning the right way, do things the right way and just go from there, because anything else, I think is fool's gold.

Long: I think, one of the other questions we really haven't touched on today, another problem that I see, in general that's crept into sports as much as it has to news, is just the problem of, I think sometimes with different media outlets their own bias that they bring to the table can be, I think, a real problem to getting the factual information out there that we want in the way that a good journalist would want to do… how much of a battle is that today, where different media have their own idea of how the news or how sports should be told.

Moore: Well, it sounds like you could have been part of my lecture here last month, because I talked about this.

Long: I wish I'd have been there

Moore: I always tell… in my class I have a whole session on this, and I always tell the students that the first thing you should do, and this isn't only journalism, this is life in general, is find out where the sacred cows are, because the sacred cows are there, and it's because all these news entities nowadays are owned by somebody or run by somebody. First let's take ESPN, and I hope nobody from ESPN is listening here because they send me a paycheck, but, I mean ESPN is basically owned by Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse, Disney World, the happiest place on earth. So do you think they want a lot of negative things? No. You may think that ESPN is being critical but they're not being as critical as you think, one of the things I point out to students all the time is that we only write about 30% of what we know, 70% we don't write about for various reasons, but a lot of it, is what you're alluding to, is because of who you're working for, you got to be very careful of who they are in bed with, and what's going on. It's not journalistically ethical but that's just the way it is.

Long: John Bailer, we've got time for a couple more questions from you and Richard.

Bailer: So, if someone is thinking about a career in sports journalism, what are some of the skills that you might recommend that they dig into, what courses they might take to increase their skills, not only in writing, but maybe in terms of doing some… understanding some of the analytics that might be relevant for the sports.

Moore: One of my constant things that I tell students, and I just did this earlier today, you should…we were talking about the importance of reading, writing and reading… and I said that what you should read is, everything. To become a good journalist, not just sports journalist, but become a good journalist, you have to be proficient at everything, so that includes analytics, everything. Certainly now, you got to, you have to become very very knowledgeable, and one reason you have to become very knowledgeable is because of the obvious that the more knowledgeable you become the better you become, but we are in a world that is changing very quickly and the numbers are a big part of that, so if you are not keeping up with the times, and knowledge of what's going on, and in this case, the numbers aspect when it comes to sports, you're going to be left behind. So I would say, it's basically that, it's that besides the writing, and the reading of course, just be knowledgeable of everything and keep your head on the swivel.

Long: Richard Campbell

Campbell: So, should journalism majors take statistics?

Moore: Oh, no question about it, I know they don't want to hear that, but yes. Yeah, anything that involves numbers, anything that involves anything for that matter, because, think about it, every aspect of society, when you talk about sports writing, takes place in sports writing, you know, the good the bad and the ugly, and certainly the numbers have gotten to be a huge part of it.

Campbell: And I ask it because sometimes we have journalism students who fear numbers, I mean but they end up having to write stories that have numbers in them and we want them to do the best job they can.

Moore: Well, here's one aspect of it, let's look at the numbers. Look at the salaries, we're talking about huge salaries in sports, you've got Kobe Bryant who's making 25million dollars, and then you've got to ask yourself, well first you've got to know about the numbers that are involved in that, you've got to know about the salary cap, you've got to understand about how that works nowadays, and the ramifications of that. You have to understand why Kobe Bryant is getting 25 million dollars, according to this last year. You got to know, here's a guy who once scored 81 points in a game, the second highest point total in the history of the NBA. Clayton Kershaw the pitcher of the LA Dodgers, ok, the numbers involved with him. ERA is so huge in baseball, here's a guy that's ERA was under 2, two straight years and last year he blew up to like 2.11, blowing up, I'm being facetious, so yeah, those are all numbers that you've got to know because when you're a sports writer, and again going back to the big picture, salaries. Salaries have gotten so huge you have to know the reasons behind why they're getting these increased salaries, and that's where the statistics come into play

Long: National Sports columnist and commentator Terence Moore has been our special guest on Stats and Stories today. Terence, thank you very much for your insights, we greatly appreciate it.

Moore: Thank you.

Long: And if you'd like to share your thoughts on our program, you can send an email to us at Stats and Stories at miamioh.edu. Be sure to listen for future editions of Stats and Stories where we explore the statistics behind the statistics and the stories behind the statistics.

Rosemary Pennington: Much of the United States is buried under snow and ice, leaving many dreaming of spring. For some that dream of spring brings with it a longing to hear the crack of a ball on a bat or the taste of peanuts in a ballpark. With the spring thaw comes baseball season and, with it, the inevitable number crunching associated with the sport. Data and baseball is the focus of this episode of Stats and Stories, where we explore the statistics behind the stories and the stories behind the statistics, I’m Rosemary Pennington. Stats and Stories is a production of Miami University’s Departments of Statistics and Media, Journalism and Film as well as the American Statistical Association. Joining me is panelist John Bailer, chair of Miami’s statistics department Richard Campbell is away today. Our guest today Christopher Phillips. Phillips is an historian of science at Carnegie Mellon University. He is the author of Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know About Baseball and The New Math: A Political History. His work has been featured in the New York Times, Time.com, New England Journal of Medicine, Science, and Nature. Phillips is also the General Editor of the Encyclopedia of the History of Science and an Associate Editor for the Harvard Data Science Review. Chris, thanks so much for being here today.

Phillips: Thanks so much for having me.

Pennington: Your book scouting and scoring looks at the history of the use of of data numerical analysis and baseball, why did you feel compelled to write that book.

Phillips: Well I think for many of us baseball has become kind of the paradigmatic example of a new way of knowing that it's the same kind of database way of knowing, taking over from the way things used to be done, which of course the new folks thinks is superstitious or religious in nature. And so we think of these as two very different cases but what I was really interested in is that when I started looking at baseball. It seems like the folks who did it the old way actually had a lot in common with the people who did it the new way. That is to say, they tried to reduce things to numbers. They tried to make reliable inferences on the basis of data. They tried to think carefully about what would be good predictors of the future. And so part of what I was just interested in is why do we think of these as two really different ways of knowing. And actually what do they look like on the ground when you're trying to predict who's going to be a great baseball player.

John Bailer: I liked how you framed it in your, in your writing as scouting versus scoring, you know, could you just define those for us and talk a little bit about why did you sort of glom on to those ideas.

Phillips: Exactly. So those are the, the two groups that are supposed to be enemies or the folks who come in, using the data that is to say the scores who traditionally keep score many people might keep score in baseball games or be familiar with all the stats that are on the back of baseball cards, or you know kind of that they are familiar with from fantasy leagues, and then scores are supposed to be the other end of the spectrum right this kind of almost always male old guys who sit on the stadium and they wear hats and they watch the game and then they choose to gars, and they try and pick out which of the players are going to be successful in the future, and couldn't be different ideas to groups. And so what I'm interested in are the ways in which they're different, but also the ways in which they're similar, you know, the kind of times that they're both trying to find reliable ways of taking past data and predicting the future on that basis.

So, good enough, just a quick follow up to that. So I just was thinking back on all the times I used to do scoring at soccer games. And, and there was there was the subjective components, you know, because there was, there were lobbying by players like I was sure I had an assist on that. Yeah, just the the subjectivity that components there that could play out in terms of how you do scoring. I hadn't really been thinking as much about it until I was reading your article and thinking about the the idea of errors versus hits, and the consequences of some of the subjectivity of it so I was wondering if you could just weigh in a little bit on on that aspect of the subjectivity in the scoring process.

Phillips: Well you know well from when you judge something to be a kind of success for one player it usually means somebody else screwed up. And so, there's always this kind of zero sum nature to most sports scoring. And the way, scoring and baseball was set up is that there, there's always it's the credit to one team as a debit to the other. So when you give a player a hit, what you're saying is that the player deserved to get to first base right you're saying but it wasn't a fault of the other team, but when you're giving a team an error it's actually the player does not deserve to get on base and so one of the interesting things about statistics is that it's kind of miraculous in baseball that we think of these things as objective at all, because at the heart of almost all these judgment calls is a person who is watching the game and deciding who to give credit to. And then, of course, when they're aggregated and compiled and we analyze them then we forget the origin of just the basic statistics is not a fancy statistic it's basic it's just the head, but it comes from people. It comes from a judgment call.

How do you, how do we get, you know, the casual fan or or someone who's interested in the sport to understand that because I do think there are moments where you know people see these stats and they imagine that they are these things that sort of come out of the ether, that frame what is good performance and what's not. And yet sort of forgetting all this subjective things that went into the construction of it, how do we need to communicate that to the guy who's showing up, you know, Reds stadium on a, on a Friday to watch a game to understand like, you know, that's not as objective maybe as you might think it is.

Phillips: Well I think when you watch a baseball game there's a lot of time to chat. And one of the good things you can do is that you watch a play and you like, how did that happen, you know, who deserves to get credit for that you know so when a ball gets hit hard between two players you can blame the pitcher, you can get a credit to the batter you can blame the players for being out of position. And so a lot of these kind of informal conversations, one of the natural results of them is that you might keep score differently than when my wife and I go, well we always debate you know whether it's credited because she has a very high standard. And so people not playing very well and she thinks, oh no he should have definitely gotten that, so I think sometimes it's just, we're so familiar with separating out these numbers as if they have kind of been God given in a certain way, instead of really thinking about the fallible processes by which all data of any kind, are made, but certainly baseball data, but I find it baseball you just start the conversations didn't look like he tried that hard did he on that one.

Bailer: You, you talked a little bit about the idea that that if you push back in time and talked about the people that were scouts or the scores that there were some similarities and differences that you, you know, could you could you talk a little bit about some of the similarities that that came out that might surprise us, perhaps, and some of the differences that that you saw, for sure.

Phillips: So one of the similarities that I think surprises. A lot of people is that the scouts actually from the 1960s onward would assign every skill a baseball player had a number, and then they'd average them together and add them up and so you get an overall what's called an overall future potential, and ofp, and so the reason why they did this was when you're drafting players and professional baseball, you have to draft players. Every team gets a pick and you go through and so you have to have a rank order list. Everyone you're potentially interested in. And the easiest way to create a ranked list is to actually create a single number for each player. And so in scouting Of course they might talk about it as this impressionistic thing but in the end of the day they put a number on every single player. And in fact, the, the fun thing I think about it is that they are in more audacious than the counters you know the baseball stats are mainly counting, but what they're doing is actually quantifying skill and then averaging into an overall skill. And so one of the kind of ironic things is you could make the claim that actually scouts are way more quantifying than baseball cores, in a certain sense.

Pennington: I was telling some friends that I was, and we were going to do this copy of this conversation, and they immediately went to Moneyball. And so, might want one colleague if you can answer this would like to know if now that everybody's money balling if small market teams are going to be competitive. So if you can answer that that would be great. But my question is, I think, I think that the history is ation of the use of data in baseball is really interesting to me because I think that's a general response. When people talk about data in baseball is to immediately go to Moneyball as though data had never been used in baseball before, so I want Why, why do you think is it just the popularity of Moneyball that is sort of framed that or is it just has the sport obscured the data somehow.